Integration Patterns: Saga Transactions

The Saga pattern allows you to defend against data loss, dropped orders, and confused (or grumpy) customers. While useful, the Saga pattern is tricky to get right without an orchestrator.

This is the first part in a five-part blog series on useful Integration Patterns. This blog series will help you build real-time, responsive applications and microservices that produce predictable results and prevent the Grumpy Customer Problem.

- [This Post] Saga Transactions

- The Transactional Outbox Pattern

- Queuing

- Retries and Dead-Letter Queues

- [Coming soon] Callbacks and External Events

The Saga Pattern

At a technical level, the Saga Pattern allows you to perform distributed transactions across multiple disparate systems without 2-phase commit.

In plain English, it is a tool in the belt of a software engineer to prevent half-fulfilled bank transfers, hanging orders, or other failures which would result in a Grumpy Customer.

The "Saga" pattern gets its name from literature and film, wherein a "saga" is a series of chronologically-ordered related works. For example, the "Star Wars Saga."

Use Cases

Business processes often need to perform actions in two separate systems either all at once or not at all. For example, you may need to charge a customer's credit card, reserve inventory, and ship an item to the customer all at once or not at all. If the payment went through but shipping failed, we would see the Grumpy Customer Problem yet again.

The Saga pattern is appropriate when:

- A business process must take action across multiple separate systems (legacy monoliths, microservices, external API's, etc),

- Each of those actions can be undone via a "compensation task", and

- All actions must logically happen together or not at all.

It's also worth noting that a different flavor of the Saga pattern can also be used in long-running business processes. In a past job, for example, I worked on a project that implemented the Saga pattern to handle the scheduling of home inspections. In this case, the task of finding an inspector to show up at the home and confirming a time with the homeowner needed to be performed atomically.

Implementation

While Saga is very hard to implement, it's simple to describe:

- Try to perform the actions across the multiple systems.

- If one of the actions fails, then run a compensation for all previously-executed tasks.

The compensation is simply an action that "undoes" the previous action. For example, the compensation for a payment task might be to issue a refund.

Case Study: Order Processing

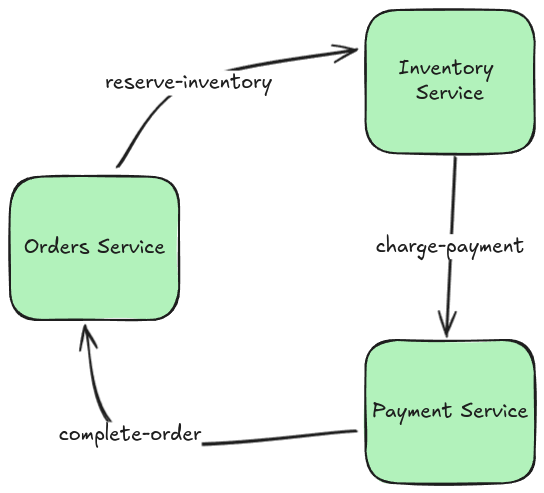

Let's take a look at a familiar use-case: an order processing workflow involving the inventory service, and the payments service. (The orders service is involved implicitly.) As they would in a real world scenario, all of our services live on separate physical systems and have their own databases.

In this business process, we first reserve inventory for the ordered item. Next, we charge the customer's credit card.

If charging the credit card fails, then we have a problem: we've reserved inventory but not sold it.

Our services need the following functionality. In SOA, these would be endpoints; in LittleHorse, they would be TaskDefs:

create-order: creates an order in thePENDINGstatus.reserve-inventory: marks an item as no longer available for sale.charge-payment: charges the customer.release-inventory: marks an item as available for sale again.cancel-order: marks an order asCANCELED.complete-order: marks an order asCOMPLETED.

Using Message Queues

Using message queues, the happy path looks like the following:

The above image assumes the choreography pattern, in contrast to the orchestrator pattern. The orchestrator pattern is a ton of work and involves writing something that very much resembles LittleHorse!

- Orders service calls

createOrder(). - Orders service publishes to the

reserve-inventoryqueue. - Inventory service reads the message and calls

reserveInventory(). - Inventory service publishes to the

charge-paymentqueue. - Payment service charges the credit card.

- Payment service publishes to the

complete-orderqueue. - Orders service consumes the record and calls

completeOrder().

In just the happy path, we have strong coupling already between our services in three places, and we have three message queues to manage.

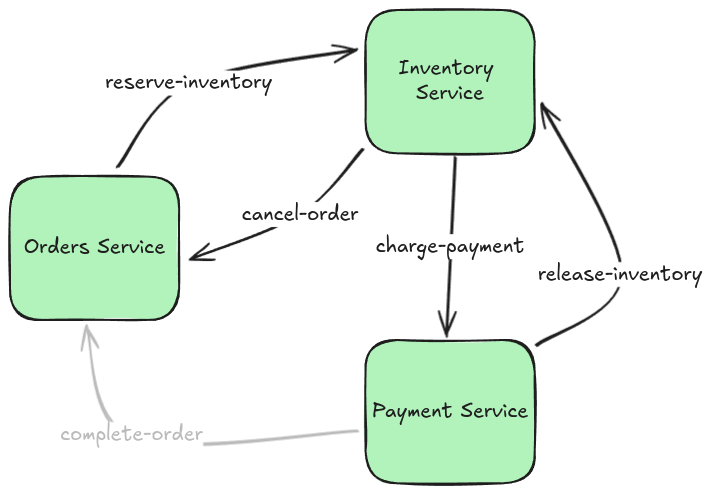

But now we need to release the inventory and cancel the order when the payment doesn't go through. So the flow looks like this:

- Orders service calls

createOrder(). - Orders service publishes to the

reserve-inventoryqueue. - Inventory service reads the message and calls

reserveInventory(). - Inventory service publishes to the

charge-paymentqueue. - Payment service charges the credit card unsuccessfully.

- Payment service publishes to the

release-inventoryqueue. - Inventory service reads the record and calls

releaseInventory(). - Inventory service publishes to the

cancel-orderqueue. - Orders service consumes the record and calls

cancelOrder().

We still haven't even considered the case when the reserve-inventory step fails and we need to catch that exception and handle the order. For the sake of brevity, we will leave that out.

Now, we have five different message queues that we have to wrangle with. We can also see that the overall business flow has started to leak across all of our different services.

One thing we are ignoring in this blog post is reliability: to make this setup production-ready, we would also have to ensure that updates to the internal databases of the services are atomic along with pushing messages to the message queue. We will cover that in next week's post (along with how LittleHorse takes care of that for you).

Using LittleHorse

Using LittleHorse, in java, this whole workflow could look like the following. This is real code that does indeed compile and replaces the need for all of the complex queueing logic we had above.

public void sagaExample(WorkflowThread wf) {

var item = wf.addVariable("item", STR);

var customer = wf.addVariable("customer", STR);

var price = wf.addVariable("price", DOUBLE);

var orderId = wf.addVariable("order-id", STR);

wf.execute("create-order", orderId);

// Saga Here! (We skipped this part in the previous section due to

// complexity, but LH makes it simple enough.

NodeOutput inventoryResult = wf.execute("reserve-inventory", item, orderId);

wf.handleException(inventoryResult, "out-of-stock", handler -> {

handler.execute("cancel-order", orderId);

handler.fail("out-of-stock", "Item was out of stock. Order canceled");

})

NodeOutput paymentResult = wf.execute("charge-payment", customer, price);

// Saga here again!!

wf.handleException(paymentResult, "credit-card-declined", handler -> {

handler.execute("release-inventory", item, orderId);

handler.execute("cancel-order", orderId);

handler.fail("credit-card-declined", "Credit card was declined. Order canceled!");

});

wf.execute("complete-order", orderId);

}

Instead of managing five message queues and five strongly-coupled integration points between microservices, all we need to do is register the workflow, define truly modular tasks, and let LittleHorse take care of the rest.

Wrapping Up

The Saga Pattern is one of five tools we will cover in this series on avoiding the Grumpy Customer Problem. It's simple to understand but painfully complex to implement. Fortunately, LittleHorse makes it easier!

A careful reader, or anyone who reads my rants on LinkedIn, might note that in order to make the order processing workflow truly reliable, we would also need to do something like the Outbox pattern or Event Sourcing.

That is true, and we'll cover it in the next post (and you'll see how LittleHorse does that for you automatically!).

Get Involved!

Stay tuned for the next post on the Transactional Outbox Pattern! In the meantime:

- Try out our Quickstarts

- Join us on Slack

- Give us a star on GitHub!