The Promise of Microservices

If microservices add so much complexity, why bother with the hassle?

This is the first part of a 3-part blog series:

- [This Post] The Promise of Microservices

- The Challenge with Microservices

- Workflow and Microservices: A Match Made in Heaven

We've all heard of microservices, but unless you've read copious amounts of Sam Newman and Adam Bellemare's writings, you might be wondering whether, when, and why you should adopt them. In this blog post, we will examine the halcyon land promised by microservices.

Microservices have been deployed widely across many large enterprises, most notably Netflix, Uber, Shopify, PayPal, and others. As we will discover throughout this blog series, a microservice architecture is mandatory once you reach a certain size of company, and it's probably overkill for a 12-person startup. The gray area inbetween is the interesting part!

What are Microservices?

The term "microservices" refers to a software architecture wherein an enterprise application comprises a collection of small, loosely coupled, and independently deployable services (these small services are called "microservices" in contrast to larger monoliths). Each microservice focuses on a specific business capability and communicates with other services over a network, typically through API's, streaming platforms, or message queues.

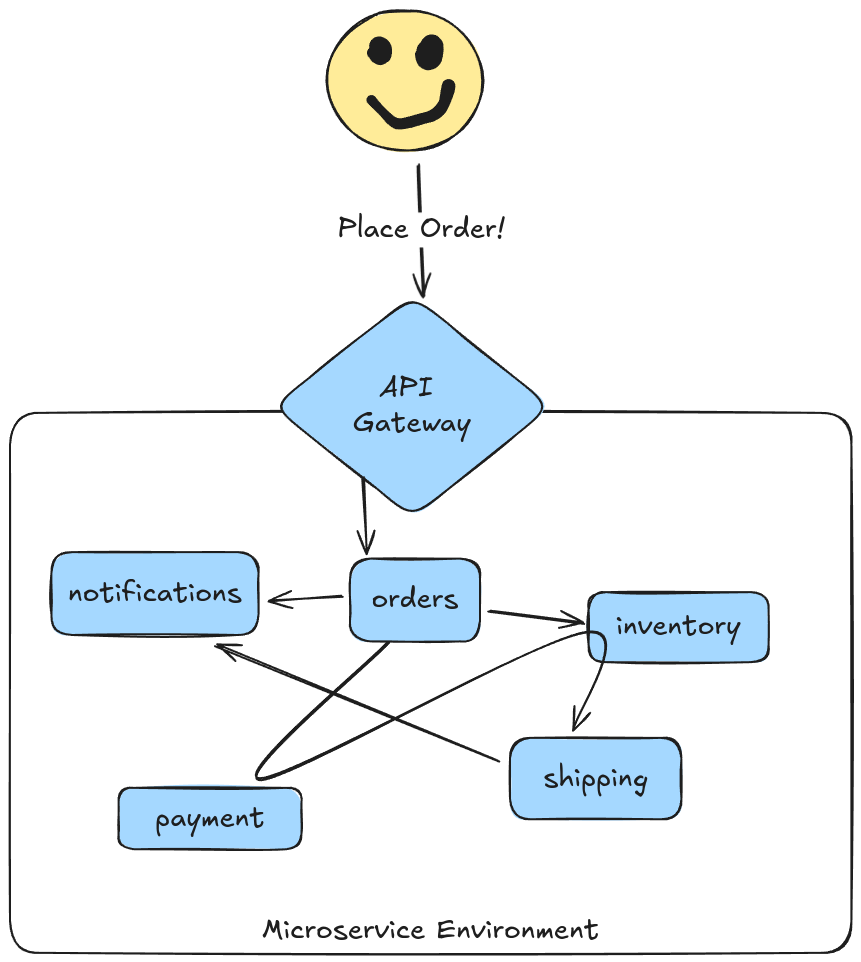

In practice, this means that a user interaction with an application (such as placing an order) might trigger actions that occur in many small, independently-deployed software systems, such as:

- A Notification service

- An Inventory Management service

- A Payments service

- An Order History service

From the user (client) perspective, one request is made (generally through a Load Balancer, API Gateway, or Ingress Controller) but that request may ping-pong between multiple back-end services and may also result in future actions being scheduled asynchronously:

In contrast to microservices, a monolithic architecture would serve the entire "place order" request on a single deployable artifact:

In Domain Driven Design, accidental complexity refers to the unintentional complexity that you introduced to your architecture (deployments, service interactions, third-party dependencies, etc.). Rule #1 of maintaining software systems is to avoid introducing accidental complexity as much as possible.

Simply by looking at the visuals above, microservices add a significant dose of accidental complexity to your architecture (more on this in next week's post!). Given that, what benefits would make up for the extra complexity introduced by microservices?

Why Now?

I would be first to admit that microservices bring with them a series of headaches around cost, observability, maintenance, and ease of evolution (otherwise, I would not have founded LittleHorse Enterprises!). However, microservice architecture plays a vital role in addressing two critical trends reshaping the software development landscape today:

- Increased digitization of companies in all business sectors (accelerated by the rise of AI).

- Elasticity of cloud computing.

Increased Digitization

The level of digitization expected of businesses in order to compete in the modern market has drastically increased: IT teams must build software that interfaces with an ever-expanding list of external API's, legacy systems, user interfaces, internal tools, and SaaS providers.

For example: in the early 2000's, it was perfectly acceptable (even expected) for a passenger to book airline tickets over the telephone or through a travel agency. However, such an experience would be unheard of today and would immediately hobble an airline who provided such poor digital services.

In addition to using automation to provide better customer services, companies are generating, processing, and analyzing massive amounts of data. For example, grocery stores with razor-thin margins analyze seasonal consumption patterns in order to optimize inventory and prevent costly food waste.

These trends have coincided with (or caused, I would argue) a proliferation in the number of 1) software developers, and 2) software tools and API's found within companies in all industries, leading to two new problems:

- Allowing large teams of software developers to productively work on an enterprise application in parallel (without stepping on each others' toes).

- Ensuring that business requirements are effectively communicated to the entire (larger) software engineering team.

Cloud Elasticity

As the importance and quantity of digital software systems exploded over the last two decades, so has the availability of nearly-infinite compute power delivered through cloud infrastructure providers such as AWS.

The promise of elasticity, or the ability to quickly spin compute resources up or down according to load and only pay for what you use, is unique to the cloud: for on-prem datacenters, spinning up new compute means buying new machines from Sun Microsystems (hopefully not Microsoft!), and scaling down compute means trying to sell them off on the secondary market. (Ask my father about how that went for a lot of people in 2001.)

Beyond scaling up and down, elasticity enables different deployment patterns that did not exist before. Whereas pre-cloud enterprises had dedicated and centralized data-center teams who were in charge of running applications, the accessibility of cloud computing gave rise to the DevOps movement. This has empowered smaller teams of software developers to take on the task of transferring software from "it works on my laptop!" to "it's now deployed in production!"

Why Microservices?

Despite the extra complexity it brings, the microservice architecture can more than pay for itself by ensuring organizational alignment and allowing enterprise architectures to take full advantage of the cloud's elasticity.

Organizational Alignment

As discussed earlier, the business problems that software engineering organizations must solve today dwarf those that were solved in the 1990's, and so do the software engineering teams that tackle those problems.

I am not belittling the engineers of the 90's; the problems they solved were arguably much harder than the problems we face today, and there were fewer engineers to face those problems. However, it is a fact that users expect more digital-native experiences today than they did twenty years ago.

By breaking applications into smaller services, we can accomplish several important things:

- Break up our software engineering team into smaller teams which are each responsible for individual microservices.

- Allow different components of a system to be developed with separate tech stacks and released independently.

Engineering teams of over a few dozen engineers working on the same deployable piece of software is a recipe for inefficiency. Merge conflicts, arguments over tech stack, slow "release trains," and excessive intra-team coordination are just a few problems that arise. However, by breaking your application into smaller microservices, you can also break up your engineering organization into smaller, more efficient teams each in charge of a small number (prefably one!) of microservices.

As an added benefit, properly-designed microservice architectures can follow the principles of Domain Driven Design. Ideally, a single microservice corresponds to a Bounded Context inside the business. This enables a small piece of the technical platform (a microservice) to be managed by a small team of software engineers, who collaborate closely with subject-matter experts and business stakeholders within a very specific domain of the business. Such close collaboration can foster better alignment between business goals and the software produced by engineering teams.

Moving Faster

Microservices can allow developers to move faster by enabling continuous delivery and independent deployment of services. In a monolithic architecture, releasing a new feature or fixing a bug typically requires redeploying the entire application. Since microservices allow smaller pieces of your application to be deployed independently, engineering teams can iterate faster and deliver incremental value to business stakeholders.

These positive effects are amplified by the advent of cloud computing. Since deploying a new application no longer requires buying a physical machine and plugging it into your datacenter but rather just applying a new Deployment and Service on a Kubernetes cluster, it is now truly feasible for small teams of software engineers to own their application stack from laptop-to-production (obviously, within the guardrails set by the central platform team). Furthermore, cloud computing is a pay-as-you-go (and often even pay-for-what-you-use) expense rather than an up-front cost. Therefore, the dollar cost of infrastructure required to support microservices is much lower today than it would have been before the advent of cloud computing and kubernetes.

Conclusion

The microservice architecture is not just a Twitter-driven buzzword but rather a way of designing system that has several real advantages. For most organizations with over two dozen software engineers, building applications with microservices is not an option but rather a necessity. However, those advantages come with a cost.

We will discuss those challenges in next week's blog post...in the meantime, though, join our Community Slack to get the latest updates!